I really like David Brooks...

Replies sorted oldest to newest

Thanks for the great article DDoc. ![]()

A helping hand for those that don't want to use up one of their free viewings this month:

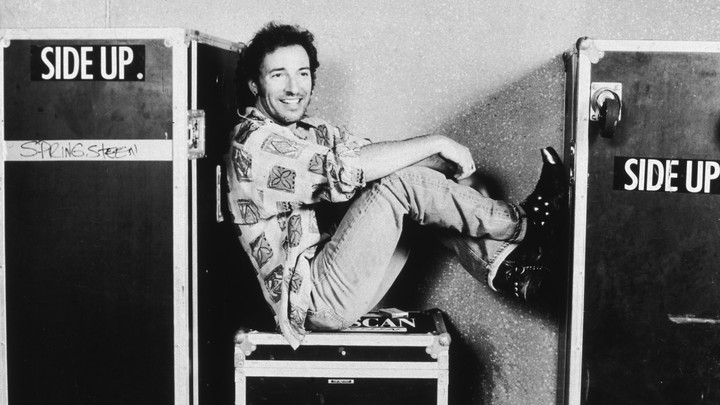

Bruce Springsteen’s Playlist for the Trump Era

“I don’t know if our democracy could stand another four years of his custodianship.”

It’s been 20 years since Springsteen wrote “American Skin (41 Shots),” a powerful song about the police killing of a black man. I thought it might be a good idea to check in with Bruce, to get his reflections on this moment and on music in this moment. Here’s a slightly edited transcript of our conversation, which took place on June 9. (Bruce’s full playlist is available on Spotify.)

David Brooks: We’ve got people marching in the streets. We’ve got great tumult. What do you see? Are you optimistic or pessimistic about what’s going on out there?

Bruce Springsteen: I don’t think anybody truly knows where we’re going from here yet. It depends on too many unknowns. We don’t know where the COVID virus is going to take us. We don’t know where Black Lives Matter is going to take us right now. Do we get a real practical conversation going about race and policing and ultimately about the economic inequality that’s been a stain on our social contract?

And of course, nobody knows where our next election is going to take us. I believe that our current president is a threat to our democracy. He simply makes any kind of reform that much harder. I don’t know if our democracy could stand another four years of his custodianship. These are all existential threats to our democracy and our American way of life.

If you look at all this, you could be pessimistic, but there are positive sides in each of these circumstances. I think we’ve got hope for a vaccine. I think any time there is a 50-foot Black Lives Matter sign leading to the White House, that’s a good sign. And the demonstrations have been white people and black people and brown people gathering together in the enraged name of love. That’s a good sign.

What’s more, our president’s numbers appear to be crashing through the basement. That’s a good sign. I believe we may have finally reached a presidential tipping point with that Lafayette Square walk, which was so outrageously anti-American, so totally buffoonish and so stupid, and so anti–freedom of speech. And we have a video of it that will live on forever.

David Brooks: How music made Bruce Springsteen

I have the feeling of optimism about the next election. I think it’s all these kids in the street that are inspiring the most hope in me. And the fact that these are demonstrations that are going on around the world. I think it’s a movement that ultimately is going to be about more than police violence, and George Floyd, may he rest in peace.

Brooks: Let’s talk about some of the big subjects. These events have been yet another unveiling of racial injustice, racial division, and racial inequality. You’ve been singing about this for a long time. I remember in your song “My Hometown,” you talked about racial tension in the high school you grew up in. How do you think we’re doing overall? Do you think we’re making progress?

Springsteen: If you look at some of the harsh events in the past weeks and then back to even just the recorded instances of oppression and police violence, you’d say we’re doing very badly. You could be very pessimistic. But on the other hand, I had a funny experience. When I watched the president march to St. John’s and pose with his Bible and his phony all-white contingent, it didn’t look real. Because it wasn’t real. That is not the America of today. That culture, which keeps black people invisible, is gone.

In the present moment, if black people are not visible, that’s not acceptable. And I think that’s a sign of progress. When you see the Democratic side of the House filled with brown people and black people, straight people and gay people, and then you look at the Republicans, who appear unchanged by history at this moment? They look ridiculous. And despite their current power, they look like a failing party.

If you look at the long narrative, like a half century ago when I was 20 or in 1968, when I was 18, you would say there have been great improvements—the civil-rights movement, the Voting Rights Act, the Obama presidency. Of course, there’s a constant pushback to whatever progress gets made, by a reactionary element. But I feel that that’s smaller now than at any time in the past, and it’s diminishing. It’s folks who see themselves being left behind by history and losing status, and it’s forces within the Republican Party and in society that are intent on keeping the power balance of the nation in one place, when that’s simply going to be impossible.

So I would say there have been a lot of improvements, but obviously we have a long way to go. There is the classic Martin Luther King quote: “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” I still believe that. But it just does an awful lot of zigging and zagging along the way. And it feels way too slow for our current times.

But we’re having a national discussion of police behavior that’s been so long overdue. It’s going to be painful, but I think it’s going to have positive effects. In the video age, police misconduct—unprovoked violence, murders—can’t be ignored or hidden. The president can pretend it’s all not happening, and that George Floyd is smiling down from heaven because of the job reports this week. But every American, and I believe the whole world, can see right now that the status quo is not okay. And that’s progress. I have a feeling that things are better now and are going in the right direction, despite or because of our current moment of some chaos.

Brooks: We’re not going to have only conversation here; we’re also going to hear a little music. And these are songs you selected to enrich the moment and maybe give a deeper understanding of what’s going on. The first song you selected is “Strange Fruit” by Billie Holiday.

Springsteen: It was written by Abel Meeropol in 1937. So imagine writing “Strange Fruit,” a song about southern lynching, and getting a popular singer like Billie Holiday to sing it in 1939. That was a very controversial recording. Her label, Columbia, did not want to release it. And she released it on another label.

It’s just an epic piece of music that was so far ahead of its time. It still strikes a deep, deep, deep nerve in the conversation of today.

Springsteen: When I started, I self-consciously saw myself as an American artist and as an average American. I figured I had a talent that allowed me to create a language in which I could speak about the things that concern me and that I felt were of concern to the place that I lived—to my neighbors and the people that I’d grown up with. I don’t know if I would call it a political point of view, but I had a point of view when I was very young, and I always viewed popular music as a movement towards greater freedom. Great music brings greater freedom …

I don’t think there will ever be one music that’s going to tell the full story, the full American story, again. The culture is too fractured right now. But I believe it’s the artist’s duty to proceed as if that above statement is untrue. To proceed as if it’s possible to have a monocultural moment and to write something and to record something that is deeply meaningful and exciting and will reach the whole nation and change the culture. You’ve got to go ahead on that impulse, you know.

But I think from here on in, the American musical conversation is going to be a cacophony of rap and pop and Latin music and so on, and there’ll probably even be some room for an old guy and a little bit of rock music. On my radio show on SiriusXM, I try to include all those different voices. It’s the only way to tell the American story that I remain committed to doing.

Brooks: One of the songs you selected is the Paul Robeson version of “The House I Live In.” This was a song originally written to combat anti-Semitism, and Robeson told it in a new way.

Springsteen: The Robeson version is quite, quite beautiful. He was an interesting guy. He was blacklisted during the McCarthy era. He was an anti-fascist and took part in the early civil-rights movement, supported the Loyalists during the Spanish Civil War, and was a stage and film actor also. He had this incredible baritone that was just kind of room shaking. And this, once again, is a song written by Abel Meeropol. I don’t know exactly who he was, but he was the Bob Dylan of his time. He was writing incredible music. And it’s just a beautiful and powerful piece of music.

Brooks: Let’s talk about social change. Every few decades, we seem to have moments of convulsive change. We had such a moment in 1968, when as you mentioned, you were 18. And a lot of people think this is another of those moments. How does this feel compared to 1968?

Springsteen: Yeah, there are similarities. I certainly felt them a few weeks ago when the SpaceX rocket was going up and cities were burning. I had a 1968 flashback.

But I think, as President Barack Obama said in his speech recently, that there are great differences. There was an unbridled rage in 1968 that isn’t quite there today to the same degree. The level of violence, as bad as it was last week, was noticeably less than in ’68. And the protesters are younger. They’re much more diverse.

50 years in photos: A look back at 1968

White and black people were not burning down Newark or Asbury Park together in 1968. That was not happening. The outrage and the feeling of “enough is enough” is similar. But all in all, I think it’s different protests for different times. In ’68 we had assassinations. We had wars in Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia. We had the rise of the “southern strategy” to counteract the rise of the civil-rights movement, which all led to Nixon and impeachment—and which should have actually happened here, if not for the gutlessness of the Republican Party.

Brooks: Let’s go to your next song. It’s “Made in America,” by Jay-Z and Kanye West. This is off their Watch the Throne album.

Springsteen: Yeah, I love this song. It’s so soulful and beautiful.

Brooks: You’ve written dozens of what I guess, if you’re comfortable with the label, could be called protest songs. They talk about social evils. They talk about wrongs. “The Ghost of Tom Joad” and so many others. Probably your most prescient song was “American Skin,” which most people know as “41 Shots.” And what’s interesting about that song, and I’m curious to ask about just how you write political music, is that it has a political message in response to a police shooting of a young African American guy.

But it’s also got different vantage points. You’ve got a black mother talking to her son about how to stay safe. You’ve also got the vantage point of the cop. So how do you keep the ambiguity of art, but also make it a clear political statement?

Read: The Trump protest-song boom, in the eye of history

Springsteen: Well. I never looked at my music as protest songs. I always tried to write what I thought were complicated character studies that had social implications, because I believe you have to create complex characters that you breathe creative, three-dimensional life into. And that’s how you find the truth in something.

“American Skin” came about while I was on my way to Atlanta and New York. It was the last two shows of the tour, and I wanted to write something new. We played it in Atlanta, which was a great place to debut it, you know. But by the time we got to New York and before we had even played it, it exploded in the press. It was tremendously controversial with some of the police unions. And this was a song—we have to understand—nobody had heard yet. But there was a big brouhaha about it. A lot of the people who had strong opinions about that song simply never heard it. And if they did hear it, they didn’t really listen to it, because it was quite a balanced picture of that incident, the shooting of Amadou Diallo.

It’s one of the songs I am most proud of. Diallo’s family came and saw his tribute at Madison Square Garden. There was some tussle when we played it. I got shown the New Jersey state bird by a group of police officers, but it was all okay. There was some booing and some cheering, and it was just a part of the set at the end of the day.

But it was written out of the idea that at the heart of our racial problems is fear. Hate comes later. Fear is instantaneous. So in “American Skin,” I think what moves you is the mother’s fear for her son and the rules that she has to lay down so he can be safe. It’s simply heartbreaking to watch a young child be schooled in this way. And the officer lives in his own world of fear. He’s got a family at home with expectations and needs. They were both living pawns in centuries-long irresolution of our race issues. And with each passing year a bill arrives, let’s say, and for every year of not dealing with this issue, payment on that bill comes due, and that payment is in blood and tears, the blood and tears of us all.

Those were the stakes I thought I was writing about, and it’s one of the songs I’m still proudest of. It’s a good song. It’s lasted and it’s done its job well.

Brooks: There is a question I’ve always wanted to ask you. You’ve spent so much of your life writing about working-class men and, in particular, working-class men who were victims of deindustrialization, who used to work in the factories and mills that were closed, whether in Asbury Park or Freehold or Youngstown or throughout the Midwest. But a lot of those guys didn’t turn out to share your politics. They became Donald Trump supporters. What’s your explanation for that?

Springsteen: There’s a long history of working people being misled by a long list of demagogues, from George Wallace and Jesse Helms to fake religious leaders like Jerry Falwell to our president.

The Democrats haven’t really made the preservation of the middle and working class enough of a priority. And they’ve been stymied in bringing more change by the Republican Party. In the age of Roosevelt, Republicans represented business; Democrats represented labor. And when I was a kid, the first and only political question ever asked in my house was “Mom, what are we, Democrats or Republicans?” And she answered, “We are Democrats because they’re for the working people.” (I have a sneaking suspicion my mom went Republican towards the end of her cognizant life, but she never said anything about it!)

Read: ‘Born to Run’ and the decline of the American Dream

In addition, there is a core and often true sense of victimization that has been brought on by the lightning pace of deindustrialization and technological advancement that’s been incredibly traumatic for an enormous amount of working people across the nation. The feeling of being tossed aside, left behind by history, is something our president naturally tapped into.

There is resentment of elites, of specialists, of cosmopolitan coast dwellers, some of it merited. It is due to attitudes among some that discount the value and sacrifice so many working people have made for their country. When the wars are being fought, they are there. When the job is dirty and rough, they are there. But the president cynically taps into primal resentments and plays on patriotism for purely his political gain.

There is a desire for a figure who will once again turn back the clock to full factories, high wages, and for some, the social status that comes with being white—that is a difficult elixir, prejudices and all, for folks who are in dire straits to resist. Our president didn’t deliver on the factories or the jobs returning from overseas or much else for our working class. The only thing he delivered on was resentment, division, and the talent for getting our countrymen at each other’s throats. He made good on that, and that is how he thrives.

Brooks: A kid growing up watching Elvis and the Beatles on The Ed Sullivan Show wasn’t automatically going to turn political. What was the influence in that part of your life?

Springsteen: It came out of an instinct I had when I reached the position of having great personal license, which I did in 1975 with the release of the album Born to Run. Something didn’t feel right to me. I didn’t feel finished. I didn’t feel at home. I felt incredibly uncomfortable.

And it took me a long time to realize that personal license is to real freedom what masturbation is to sex. It’s not bad, but it’s not the real thing. And as I started on this record, Darkness on the Edge of Town, I said, I want to turn the car around. I want to go back to my neighborhood, and I want to understand the structural issues, personal issues, social issues that are pressing down hard on the people I’m writing about and still living among. That’s where what I’m looking for resides. And so that’s kind of where my politics really began to develop, out of concern for my own moral, spiritual, emotional health, and that of my neighbors.

Brooks: That brings us to our next song, which sounds like a Trump-protest song. It’s “That’s What Makes Us Great” by Joe Grushecky.

Springsteen: Joe said to me, “Gee, I wrote this song. It’s called ‘That’s What Makes Us Great.’”

And this was right around the time of the MAGA movement. I said, “Well, that’s a great title.” And it is. And he said, “Why don’t you sing it with me?” And so we sang it together.

Brooks: You mentioned that when you made Darkness, you had to go back to your roots. You were on the cover of Newsweek and Time; your career blew up. You could’ve gone big and global. Instead, you went back home and local. And you’re still there. You’re still sort of in the neighborhood of Asbury Park.

Springsteen: Yeah, I’m still in New Jersey, 20 minutes away from Asbury, 10 minutes from Freehold.

So I’m still very comfortable here.

Brooks: How are those towns doing? What do they tell you about the wider American experience?

Springsteen: I’ve always felt everybody has this moral, spiritual geography, emotional geography, inside themselves. You may live in Barcelona, but you can feel you’re related to Asbury Park, some place you may never go. But if a songwriter is writing well and is writing about the human condition, you’ll take them there. They’ll get there. We have our greatest audience overseas—I think two-thirds to more of our audience now is in Europe. People are still captured by and deeply interested in America, what’s going on here and the American myth. The American story is a worldwide story, and it continues to have tremendous power.

Brooks: One final question. When you did your Broadway show, you ended it with a very direct, stark version of the Lord’s Prayer, which surprised a lot of people. It made me go back to your music and listen to old songs in new ways. You have a party song called “Mary’s Place.” But when you see it through the possible prism of faith, it’s the most happy tribute to Mother Mary ever written. I don’t know if you wrote it that way. So I just want to ask you, how do you experience holiness and the holy presences in the world right now?

Springsteen: If you look at “Mary’s Place,” it’s about going someplace where there is community and fraternity and spiritual sustenance. So that’s what that song is all about at its bottom, and that’s what most of my music is about—“The Promised Land,” “Badlands,” and the rest are all about people trying to find their spiritual and moral and social way through the world. And trying to find a place where they can build a home, where those values sustain them.

I don’t follow a lot of rituals, but I still hold a close place, probably, for the Catholic Church, just out of indoctrination and habit, I suppose. You know, despite my misgivings, my children aren’t baptized. I’ve got pagan babies, and they seem to be doing fine spiritually. They’re good, solid souls!

But I reference my Catholic upbringing very regularly in my songs. I have a lot of biblical imagery, and at the end of the day, if somebody asked me what kind of a songwriter I was, I wouldn’t say I was a political songwriter. I would probably say a spiritual songwriter. I really believe that if you look at my body of work, that is the subject that I’m addressing. I’ve addressed social issues. I’ve addressed real-life issues here on Earth. I always say my verses are the blues and my choruses are the gospel. And I lean a little heavier on the gospel than the blues. So I would categorize myself as ultimately a spiritual songwriter.

Brooks: Let’s close with a jolt of caffeine from a friend of yours—“People Have the Power,” by Patti Smith.

Springsteen: This is just purely a great, great anthem. And one of those songs I wish I’d written, but I’m really, really happy that she wrote it. I don’t think there’s a better song for this moment than this song.

(Bruce’s full playlist is available on Spotify.)

We want to hear what you think about this article. Submit a letter to the editor or write to letters@theatlantic.com.

Attachments

Damn! And I ended up using my last free viewing on it before I saw this!